Difference between revisions of "Robert Hull Fleming Museum"

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

As a teenager, I discovered the Boston Athenæum, where several plaster casts are still on display. No 19th century museum was complete without plaster casts. The Boston Athenæum is a library and a museum with a smoking room on its first floor, and a working kitchen just off of the Art and Art History stacks. Other dark and wonderful places of my childhood were The Peabody Museum and the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy, both at Harvard University, where my father worked. Here were the mysterious glass flowers—literally hundreds of cases of them, hundreds of birds from hummingbirds to ostriches, and animals tiny and huge from every continent, all with a giant whale skeleton overhead. Across the yard, at the Widener Library, I saw the dioramas of Cambridge and upstairs, the special, slanted topped vitrine constructed for the Library’s Guttenburg Bible. The interest, even the attitude of veneration assumed by my father, a book designer, made a deep impression on me. | As a teenager, I discovered the Boston Athenæum, where several plaster casts are still on display. No 19th century museum was complete without plaster casts. The Boston Athenæum is a library and a museum with a smoking room on its first floor, and a working kitchen just off of the Art and Art History stacks. Other dark and wonderful places of my childhood were The Peabody Museum and the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy, both at Harvard University, where my father worked. Here were the mysterious glass flowers—literally hundreds of cases of them, hundreds of birds from hummingbirds to ostriches, and animals tiny and huge from every continent, all with a giant whale skeleton overhead. Across the yard, at the Widener Library, I saw the dioramas of Cambridge and upstairs, the special, slanted topped vitrine constructed for the Library’s Guttenburg Bible. The interest, even the attitude of veneration assumed by my father, a book designer, made a deep impression on me. | ||

| − | In Boston also is the Warren Medical Museum, which houses the famous Phineas Gage exhibit, his skull and the tamping rod that accidentally gave Mr. Gage the equivalent of a frontal lobotomy in 1848, Cavendish, Vt. Unfortunately, the Warren Anatomical Museum, which once took up several floors in a building adjacent to the Harvard Medical School, has shrunk like a shrunken skull, and resides in an upstairs hallway at the Countway Library. There are a mere two glass vitrines and two illuminated wall cases for the entire collection—which would rival the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia if the trustees at Big Crimson weren’t embarrassed by and afraid of their own collection. I urge all of you to lobby this supposed richest non-profit corporation on planet earth to expand and display this fabulous collection of embryonic skeletons, wax models of cysts, displays featuring | + | In Boston also is the Warren Medical Museum, which houses the famous Phineas Gage exhibit, his skull and the tamping rod that accidentally gave Mr. Gage the equivalent of a frontal lobotomy in 1848, Cavendish, Vt. Unfortunately, the Warren Anatomical Museum, which once took up several floors in a building adjacent to the Harvard Medical School, has shrunk like a shrunken skull, and resides in an upstairs hallway at the Countway Library. There are a mere two glass vitrines and two illuminated wall cases for the entire collection—which would rival the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia if the trustees at Big Crimson weren’t embarrassed by and afraid of their own collection. I urge all of you to lobby this supposed richest non-profit corporation on planet earth to expand and display this fabulous collection of embryonic skeletons, wax models of cysts, displays featuring dwarfs, Siamese fetuses in formaldehyde, &c., &c., &c. |

| − | In Bridgeport, Connecticut, are the remains of the Peale—and many other—collections, all brought together in what was certainly the most popular (and the most financially successful) museum in our nations history. Of course this is none other than the American Museum of Phineas Taylor Barnum. The slivers which managed to survive the disastrous fires that plagued the great showman at several points in his career can be seen at the Barnum Institute of Science and Natural History. Here can be seen the | + | In Bridgeport, Connecticut, are the remains of the Peale—and many other—collections, all brought together in what was certainly the most popular (and the most financially successful) museum in our nations history. Of course this is none other than the American Museum of Phineas Taylor Barnum. The slivers which managed to survive the disastrous fires that plagued the great showman at several points in his career can be seen at the Barnum Institute of Science and Natural History. Here can be seen the little person, Tom Thumb’s clothing, his carriages, and the personal effects of his wife, Lydia Warren, also of small stature. A “mermaid” is on display, albeit a contemporary artist’s version, and hence a rather more sloppy and uninteresting one than a genuine, 19th century example. Barnum was famous for the “Fegee Mermaid.” It was alternately enjoyed and denounced for years. This creature inspired the exhibition of many counterparts; one was in Boston. As late as the ‘70s there was a small pavilion and a glass case at Galveston, Texas, that was the home of a mermaid. It is not known if it is still there. Harvard has its own mermaid, but, typically, won’t let anyone see it. Also in Bridgeport are Revolutionary War musket balls, shingles from the house of John Brown, swords from Saudi Arabia and opium pipes from China, to name just a very few representative items. |

Interestingly enough, our colleagues in California at The Museum of Jurassic Technology are quite biased against Barnum. This is unusual for Mr. Wilson the curator, an astounding intellect and leader in the field of the type of unique knowledge “the world may never know again.” For, on its website and through its introductory video, the exhibitions at Culver City virtually accuse Barnum of intentionally “incinerating” the amazing collections he assembled. This is simply not true. Nor is it true that he purchased the collection of the Philadelphia Museum; it had already dissolved and was owned by Charles W.’s son, Reuben Peale, in New York, when Barnum was able to acquire a portion of this collection. | Interestingly enough, our colleagues in California at The Museum of Jurassic Technology are quite biased against Barnum. This is unusual for Mr. Wilson the curator, an astounding intellect and leader in the field of the type of unique knowledge “the world may never know again.” For, on its website and through its introductory video, the exhibitions at Culver City virtually accuse Barnum of intentionally “incinerating” the amazing collections he assembled. This is simply not true. Nor is it true that he purchased the collection of the Philadelphia Museum; it had already dissolved and was owned by Charles W.’s son, Reuben Peale, in New York, when Barnum was able to acquire a portion of this collection. | ||

Latest revision as of 07:34, 30 August 2009

Contents

A Lecture at the Fleming Museum

The Traditional Museum—What It Did and How It Worked, A Summer Lecture at UVM

This is a very special show. It is highly likely that many of the items in this show have never been on public display here, or anywhere else, and it is equally likely that many of them will never be publicly seen again. [laughter] At least in a public institution. In a vitrine.

The Fleming Collection

The collection that you have the pleasure of dealing with tonight, and which my fellow curators and I have had the pleasure of dealing with for the past several months, represent items drawn mainly from the "c" or Colonial collection of Vermontiana which was translated in the 1980’s into the categories of either American, European, Decorative Art, Costume and Textile collections. Those items not focused on Vermont cultural history—the boar’s tooth necklace, Japanese wig, shrunken head and tefillin, for example, can best be described, from a 19th century vantage point at least, as Exotica.

Probably even before the influence of the Perkins family on the Fleming collection, it resembled the 19th century model, or a “magnificent gallery of débris.” When the methods of the Modern period were used in curation a great many of the disparate elements of the collection were either re-cataloged or sent to various other departments of the university. The zoölogy department, for instance, was given the taxidermic specimens, and the botany department was beneficiary of the herbarium. A great many items were simply thrown out due to “poor condition,” or due to the non-conformity of the items in question to successive waves of curatorial guidelines introduced during the 20th century.

Civil War “foraging” trophies are an example of this curatorial wrestling with consciences. A great many souvenirs of the War Between The States made their way back to Vermont when the families of Union soldiers placed furniture, money, jewelry and other valuables from Southern homes into their knapsacks and at a later date, into the Fleming collection. Catalog entries refer to these items being “gifts” but most of these items were undoubtedly stolen by occupying Union armies—including troops of the Vermont Brigade. A Typical example from the “c” catalog is the “table top...given” to a Brattleboro, Vermont, private in 1865 by a “Southern Lady.” The reason for its deaccession in the 1950s was given as its “very poor condition.” At the very least a contributing influence on this deaccession is its provenance. Theft, in a time of war.

Thankfully, not all troublesome, tattered, bug-eaten, or obscure items were removed from the collection. Some of them “discovered”, or more properly “re-discovered” for this show. (i. e.: Ira Allen's shoe buckles), some of them had been known to curators for years (the white rocks from the same stream in which Biblical David found for his weaponry, for instance).

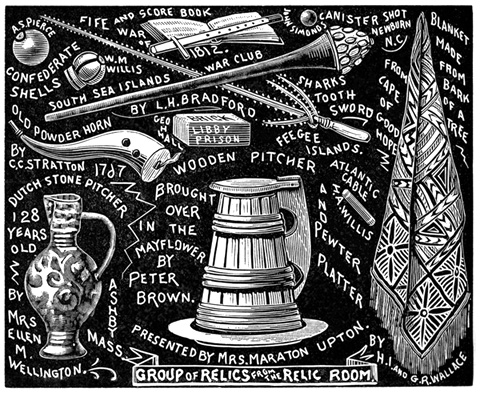

While the categories used in the “Re/Collections” show were the curator’s invention, the catalog numbers were not. Many of the items were accessioned, or at least given numbers, in successive generations. One item was found with three entirely different catalog numbers affixed to it. The assembled items, though small in number compared to the entire holdings of the Museum, are large enough to more than fill the cabinets of the Wilbur room and the result is strikingly like the “veritable graveyard-yards in which have been heaped up, with a tumulour-like promiscuousness, the remains which have been carried thither.” Here we find nails, rocks and bits of cloth, assorted animal parts and pieces of miscellaneous metal and wood. How did they get here? At first glance it would appear that we are deconstructing the entire museum experience. And yet the Allen spectacles and the shoe-buckles are significant due to their proximity to the Allen Family itself. This family looms large in Vermont, as well as University, history. In spite of appearances, there are no meaningless items here. They are all representations of the collective unconscious. Here is an example from the Colonial Collection. It is one of the missing items:

A small trunk, made prior to the war of 1812 by a small boy named Hiram Russ and given to his playmate Betsey, who in later years became his wife. Lined with old newspapers. Painted blue. Mrs. R. B. Conners, Burlington, VT.

I would hazard a guess that the writer is the daughter of Hiram and Betsey, writing down for posterity the romance of her parents—important events in the life of her family and treasured memories surely. All of the Civil War memorabilia collected both North and South consists of items literally drenched in blood and significance. The soldiers in this fratricidal war killed each other by the tens of thousands, sometimes at a distance of just a few feet. Bullets might pass through the body of the soldier next to you, causing instant death of a dearly beloved comrade—sometimes a boy no older than a teenager. It is no wonder that a shingle from a house on the fields at Gettysburg, or a tree limb with a civil war musket ball imbedded in it, was—and is—a treasured relic.

The Main Street Museum

Founded in 1992, the first Main Street Museum was in many ways site-specific, although this was only learned through hindsight. The site was downtown White River Jct., Vt.—a somewhat abandoned railroad town with much of the urban blight one would expect in a much larger town or city. White River Junction had been host to many things over the years, many of them none-too-savory. A railroad town will always attract a spectrum of humanity. It was—and is—a perfect home for an alternative museum.

We immediately attracted young and old—a broad cross-section of Vermont and New Hampshire’s citizenry: academics, art professionals—and unprofessionals, musicians, politicians, journalists, the under-employed, habitual evil-livers, and quite ordinary folks (and, it might as well be admitted; many in all of these categories were my own blood relatives). All of these and more were welcomed into a narrow storefront space that had been a silent picture theater, a restaurant with transvestite waitresses, and and an indoor miniature golf course (I’m not kidding). In this newly conceived museum, Elvis impersonators and High-Art all enjoyed equal admiration. (Or, the High-Art claimed as much admiration as it could, when competing with Elvis impersonators.) Our home was directly across the street from an American Legion Hall, and there are no better art critics. They would be completely and utterly potted when they came over and would inform us about everything from the esoteric secrets of the world to more ordinary wisdom, and some of the most innocent, and most malicious, town gossip you could ever hear.

The South Main Street incarnation of the Main Street Museum will rise at least partially, Phœnix-like, on North Main Street this time in donated space in the Tip-Top Arts and Media Building, although with less peeling paint and fewer feral cats. Finding a home for exhibits of this type will always be a challenge, and alternative museums are, by nature, at risk financially. Appreciate us while you can, and remember your kind remarks, words of criticism and encouragement mean just as much to us as money does.

The Traditional Museum

Some discussion of what I mean by the traditional museum may be helpful at this point. Let’s describe a few. I will limit myself to American museums to focus this discursion.* I grew up in Boston; and Boston is a very good town for museums. Eccentrics—crazy people—are the people who run and donate to and endow museums. Fortunately for Boston, it is absolutely awash in eccentrics. Both it and New Orleans, Louisianna are cities full of odd characters, as well as superstition and primitive customs that are observed nowhere else in the world.

As a teenager, I discovered the Boston Athenæum, where several plaster casts are still on display. No 19th century museum was complete without plaster casts. The Boston Athenæum is a library and a museum with a smoking room on its first floor, and a working kitchen just off of the Art and Art History stacks. Other dark and wonderful places of my childhood were The Peabody Museum and the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy, both at Harvard University, where my father worked. Here were the mysterious glass flowers—literally hundreds of cases of them, hundreds of birds from hummingbirds to ostriches, and animals tiny and huge from every continent, all with a giant whale skeleton overhead. Across the yard, at the Widener Library, I saw the dioramas of Cambridge and upstairs, the special, slanted topped vitrine constructed for the Library’s Guttenburg Bible. The interest, even the attitude of veneration assumed by my father, a book designer, made a deep impression on me.

In Boston also is the Warren Medical Museum, which houses the famous Phineas Gage exhibit, his skull and the tamping rod that accidentally gave Mr. Gage the equivalent of a frontal lobotomy in 1848, Cavendish, Vt. Unfortunately, the Warren Anatomical Museum, which once took up several floors in a building adjacent to the Harvard Medical School, has shrunk like a shrunken skull, and resides in an upstairs hallway at the Countway Library. There are a mere two glass vitrines and two illuminated wall cases for the entire collection—which would rival the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia if the trustees at Big Crimson weren’t embarrassed by and afraid of their own collection. I urge all of you to lobby this supposed richest non-profit corporation on planet earth to expand and display this fabulous collection of embryonic skeletons, wax models of cysts, displays featuring dwarfs, Siamese fetuses in formaldehyde, &c., &c., &c.

In Bridgeport, Connecticut, are the remains of the Peale—and many other—collections, all brought together in what was certainly the most popular (and the most financially successful) museum in our nations history. Of course this is none other than the American Museum of Phineas Taylor Barnum. The slivers which managed to survive the disastrous fires that plagued the great showman at several points in his career can be seen at the Barnum Institute of Science and Natural History. Here can be seen the little person, Tom Thumb’s clothing, his carriages, and the personal effects of his wife, Lydia Warren, also of small stature. A “mermaid” is on display, albeit a contemporary artist’s version, and hence a rather more sloppy and uninteresting one than a genuine, 19th century example. Barnum was famous for the “Fegee Mermaid.” It was alternately enjoyed and denounced for years. This creature inspired the exhibition of many counterparts; one was in Boston. As late as the ‘70s there was a small pavilion and a glass case at Galveston, Texas, that was the home of a mermaid. It is not known if it is still there. Harvard has its own mermaid, but, typically, won’t let anyone see it. Also in Bridgeport are Revolutionary War musket balls, shingles from the house of John Brown, swords from Saudi Arabia and opium pipes from China, to name just a very few representative items.

Interestingly enough, our colleagues in California at The Museum of Jurassic Technology are quite biased against Barnum. This is unusual for Mr. Wilson the curator, an astounding intellect and leader in the field of the type of unique knowledge “the world may never know again.” For, on its website and through its introductory video, the exhibitions at Culver City virtually accuse Barnum of intentionally “incinerating” the amazing collections he assembled. This is simply not true. Nor is it true that he purchased the collection of the Philadelphia Museum; it had already dissolved and was owned by Charles W.’s son, Reuben Peale, in New York, when Barnum was able to acquire a portion of this collection.

Barnum began the first aquarium in New York, and his Museum was an extremely democratic, educational place, where flora and fauna of all the continents, artifacts from every historical era, were represented side-by-side with human oddities. It is this last element of the Barnum museum, and others like it, that has been most troubling to contemporary critics and has perhaps colored the views taken of him by ordinarily quite insightful people. It may be the Wooly Horse, the Fat Woman, the Albino Family from Belgium, and the Siamese twins—to say nothing of the “Missing Link”, that have tainted the view of P. T. Barnum. In this instance, I would warn against historicism. It is simply not fair to judge individuals in the past by the values of the present culture.

All of these traditional museums relate closely to other public exhibits, most notably the Columbian Exhibition, or the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. With its monumental art and architecture, displays of contemporary art and music and its display of nearly every invention and scientific innovation of the day, it would be impossible to over estimate the importance of this fair in the intellectual and cultural life of this country as well as its influence on international opinion as well. It is known that the Perkins family visited this Exposition, but not if they purchased any of the Fleming collection there.

Closer to home, I would like to briefly describe a museum that was undoubtedly known to the curators at the Fleming, The Historical Collection & Pictures at Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth, Massachusetts. It is not known how definite the connection was between Henry Perkins (and the Eugenics Movement), and the historical artifacts in Plymouth. We know that this movement had a strong genealogical component. We surmise that Perkins at the very least would have known of this collection, either through its publications, like its catalogs, or from actual contact. The collection focuses on the Mayflower, so important to the fabricating of an American Cultural Creation Myth. Some of the items listed in it 1920 catalog are nearly identical to items in the Fleming Collection.

In the vestibule at Plymouth, with portraits and photographic representations of the Mayflower with passengers in various activities, the First Thanksgiving is given prominence. As the catalog progresses, and the case numbers and catalog entry numbers get higher, artifacts such as Governor Brewster’s Chair (Coolidge sat in it for a photo-op) and the ax of Miles Standish (its Arabic inscription was the subject of much conjecture) are mingled with artifacts of slightly more tangential quality, such as “Razors found in the Myles Standish house in Duxbury” and an “Ancient Vase belonging to the Standish Family” (donated by Mrs. Lydia Weston Field of Hartland,Vt.); Displayed in this melange of Pilgrim history are: “the cap worn by Peregrine White” (her belongings seem to be especially popular due to the cuteness factor—she was the first baby in the new colony); a “remnant of a Hoe, a Brick and other relics from the Watch-house on burial Hill in 1643-1675;” and the “barrel of a gun with which King Phillip was killed” (we wonder if this sanguinary item is still on display.)

Soon other items appear, not necessarily connected to the Mayflower, or Plymouth, or even the 17th century. For instance, the sofa which once belonged to John Hancock, an authentic “Gettysburg Relic—sword used in many battles of the civil war,” and “Arrow heads, an ancient coffee pot, [a] Pair of ancient Shoes”

So far we have been in the upper Hall. In the lower hall and annex we find “wood from a post of the English frigate Somerset, wrecked on Cape Cod during the Revolution...a Contrivance used by the California Indians for producing Fire,” and a “curious and Rare Cap worn in early times by a Sandwich Island Chief.”

Next to be seen, at least in 1920, are: “A door handle from the Barker House, Plymouth; A piece of wood from Peregrine White’s Apple Tree; Wig worn by Josiah Winslow. A piece of Mahogany from the Electrical Machine made by Benjamin Franklin; A piece of the Appomattox Apple Tree; An acorn from the tree in which Charles the Second was concealed after the Battle of Worcester; A Cane made of wood from the ship Constitution, A Chinese Razor; A Japanese Inkstand.” And what surely must be my favorite, and I quote directly from the catalog: “A Chanukah Lamp used by the Jews in the ‘Feast of Lights,’ continuing eight days (one light is added each day) Celebration occurs in December.”

The Encyclopedia as a Collection

Different methods of organizing information induces odd feelings. In this instance, the source is literary and so sweeping that the effect is literally dizzying. I speak of another type of collection—the Modern encyclopœdia. Denis Diderot was the first Modern encyclopœdist and, before the French Revolution, assembled what was a model for all to follow. The “grand caravan” of items and artifacts to be found in the traditional museum have their exact counterpart in the encyclopœdias written previously to, say, the year 1910-11. This is the date of the 11th Edition of the Encyclopœdia Britannica, last Britannica to feature initials of authors, making each entry a small, personal work of literature (some of them not so small). Reading many of these pieces produces extreme vertigo in the reader because many of them are opinionated, even biased, screeds. As an example of this, I would like to read for you the entry for “Goat”

Was the author raised in a household of exceptionally smelly goats? But 19th century audiences and reader would not have thought anything of such editorializing. We enjoy this entry for that incipient encyclopœdist himself, Diderot: Diderot, Denis (1713–1784) French man of letters and encyclopaedist, was born at Langres on the 5th of October 1713. He was educated by the Jesuits, like most of those who afterwards became the bitterest enemies of Catholicism; and, when his education was at an end, he vexed his brave and worthy father’s heart by turning away from respectable callings, like law or medicine, and throwing himself into the vagabond life of a bookseller’s hack in Paris. An imprudent marriage (1743) did not better his position. His wife, Ann Toinette Champion, was a devout Catholic, but her piety did not restrain a narrow and fretful temper, and Diderot’s domestic life was irregular and unhappy. He sought consolation for chargrins at home in attachments abroad, first with a Madame Puisieux, a fifth-rate female scribbler, and then with Sophie Voland, to whom he was constant for the rest of her life. This entry written by, “J. Mo” [Viscount Morley, of Blackburn] himself a great writer on the French Revolution and the subject, in the 11th ed., of his own entry.

We are clearly dealing here not with the neutral voice of authority—the subject is not merely Denis Diderot, but his wife, and two of Diderot’s lovers. The subject is the author’s opinion of Diederot’s personal life. And, most importantly here, the audience is considered intelligent enough to interpret this clearly biased text.

The correlation to the appreciation of museums is quite close. In the traditional museum, or object display, the opinions were quite definite: “here is the musketball from Gettysburg; the soldiers who fought and died there tore families apart.” There is a a diorama at Pilgrim Hall showing figures, the Pilgrims, digging up the Native Americans corn—stealing it, in other words. We are left on our own to determine if they were criminals or merely hungry. This is not like watching television, where we are led from one obvious visual effrontery to another, from “drink this soft drink and you’ll be cool” to “our children are our future.” In the Traditional Museum, the stimulus is much more ambiguous: what does a “Chinese Lady’s Slipper” mean, as seen at the Fairbanks Museum in St. Johnsbury, Vermont? And more intriguingly, what does this miniscule shoe mean when displayed alongside “Nails from the Holy-Land,” and pieces of “Civil War Hard Tack?” It can mean many things. What does a rock mean? Witness the hall of geology at Harvard.

People for centuries have entered holy places and seen items of cultural importance and not thought in the slightest about whether the items were “real” or not. The sum was assumed to be greater than the parts. The meaning of objects was assumed to be their proximity to historical events, and significant cultural directions.

It is clear then, that when we look backward at former Museum displays that we are traveling in foreign territory from 20th century curation methods. Whether they be “Tippo Sultan the Baboon” on Woodstock’s green, “Pip and Flip, the Oriental Twins from Peru” at Coney Island, the Pilgrim Society’s proud display of its Menorah, or the Fleming’s preservation of the bathtub of Elias Lyman (in a startling coincidence he is the same man who, in the early 1800’s built the former woolen mill in which I now live), we are lost in strange waters. How completely we are lost can only fully be appreciated standing in front of these displays—perhaps from the balcony of the Fairbanks Museum—and staring down at the pink flamingo display, or the hundreds of hummingbirds in artificial trees, and then looking up and reading the text accompanying some of the cast pitchers from Persia that describes them as “very old.” I notice that they are in a case with some Japanese shoes. The Egyptian case in back of me has a sign, “Mummies—a Way of Death.” The sensation I feel is vertigo.

References

- Phineas Taylor Barnum, The Humbugs of the World: An Account of Humbugs, Delusions, Impositions, Quackeries, Deceits and Deceivers Generally, in all Ages. New York, 1865.

- ———, Struggles and Triumphs; or Forty Years’ Recollections of P. T. Barnum, Written by Himself. Hartford, Connecticut, 1869.

- Robert Bogdan, Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. Chicago, 1988.

- Kevin Dann, “From Degeneration to Regeneration: The Eugenics Survey of Vermont, 1925-1936,” Vermont History, (Winter, 1991.)

- ———, “The Pirate Family of Lake Champlain and Vermont Eugenics,” Paper presented at the Robert Hull Fleming Museum, Burlington, 1995.

- Nancy L. Gallagher, Breeding Better Vermonters, Hanover, 1999. The authoritative work on Henry Perkins, the Eugenics Movement in Vermont, which informed so much of the Fleming Museum collection.

- Benjamin Ives Gilman, Museum Ideals Of Purpose and Method, Cambridge, 1923. (Rejects the idea of the label altogether, in chapter iv § iii.)

- Charles F. Horner, The Life of James Ridpath and the Development of the Modern Lyceum, New York, 1926.

- James Frothingham Hunnewell, Historical Museums in a Dozen Countries, “An Address Read Before the Bostonian Society at its Annual Meeting, January 12, 1909.”

- Doug Kirby, Ken Smith, Mike Wilkins, with Jack Barth, Roadside America, New York, 1992. This book, covering as it does all 50 states of this wonderful country of ours, is a must read. They even take a couple of well-deserved swipes at Harvard U, as well. They are dear to our hearts. Now (2009) mostly transposed to thier highly entertaining web-site: http://www.roadsideamerica.com

- Phillip B. Kunhardt, Phillip B. Kunhardt iii, Peter W. Kunhardt, P. T. Barnum, America’s Greatest Showman, New York, 1995. Some of the pictures of living “oddities” recently discovered for this book will lodge themselves in your brain and stay there.

- Martin Johnson, Cannibal-Land, Adventures with a Camera in the New Hebrides, Boston, 1929.

- Charles Mackay, LL.D., Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, London, 1852.

- The Photographic History of the Civil War (ten volumes), Robert Lanier, Managing Editor, Seacaucus, 1911.

- Nicole Hahn Rafter, White Trash, The Eugenic Family Studies, 1877-1919, Boston, 1988.

- Clark E. Ridpath, With The World’s People, Washington, D. C., Louis Havemeyer, Ph.D., Ethnography, Boston, 1929.

- Lawrence Weschler, David Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder, New York, 1995, Weschler’s entertaining study of the Museum of Jurassic Technology is as intriguing a book as the diminutive curatorial experiment in Culver City.

- J. G. Wood, M. A., F. L. S. (Rev.), Illustrated Natural History For Young People, Boston, n.d.