Difference between revisions of "Cape Florida Light, Key Biscayne, Florida"

| Line 241: | Line 241: | ||

*https://www.flkeysnews.com/living/article147339204.html | *https://www.flkeysnews.com/living/article147339204.html | ||

*[http://elinordewire.blogspot.com/2018/09/a-lighthouse-on-fire.html A dramatic account of the battle by Elinor DeWire, 2018.] | *[http://elinordewire.blogspot.com/2018/09/a-lighthouse-on-fire.html A dramatic account of the battle by Elinor DeWire, 2018.] | ||

| + | *https://www.facebook.com/atropicalfrontier/posts/thompson-john-w-b-biscayne-bay-cape-florida-called-irwin-thompson-by-nathan-shap/2564877170283736/ | ||

| + | |||

[[Category:Foote Family Papers]] | [[Category:Foote Family Papers]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:14, 9 May 2020

The Cape Florida Light is a lighthouse on Cape Florida at the south end of Key Biscayne in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Constructed in 1825, it guided mariners off the Florida Reef, which starts near Key Biscayne and extends southward a few miles offshore of the Florida Keys. It was operated by staff, with interruptions, until 1878, when it was replaced by the Fowey Rocks lighthouse. The lighthouse was put back into use in 1978 by the United States Coast Guard to mark the Florida Channel, the deepest natural channel into Biscayne Bay. They decommissioned it in 1990.

Within the Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park since 1966, the lighthouse was relit in 1996. It is owned and operated by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

Contents

History

First light

The construction contract called for a 65 foot tower with walls of solid brick, five feet thick at the bottom tapering to two feet thick at the top. It was later found that the contractor had scrimped on materials and built hollow walls. The first keeper of the lighthouse was Captain John Dubose, who served for more than ten years. In 1835 a major hurricane struck the island, damaging the lighthouse and the keeper's house, and flooding the island under three feet of water.

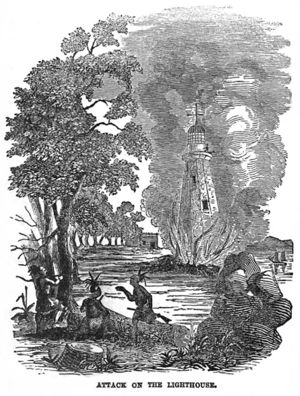

Attack on the lighthouse

When the Second Seminole War started in 1835, the Seminoles attacked the few European-American and enslaved African American, and free black, settlers in southern Florida. In January 1836 the Seminoles massacred the family of William Cooley at their coontie plantation on the New River, in what is now Fort Lauderdale.

On hearing of the massacre, the settlers on the mainland around the Miami River crossed over Biscayne Bay to the lighthouse. As the island was not considered safe, the settlers and Captain Dubose's family moved to Key West for refuge.

Later in January, Lt. George M. Bache, U.S. Navy, arrived from Key West with a small work party to fortify the lighthouse tower; they boarded up the ground floor windows and reinforced the door. On July 18, 1836, Captain Dubose went to visit his family in Key West. The assistant keeper, John W.B. Thompson, was in charge, aided by Aaron Carter, an African American.[Blank 1996, pp. 39-41, Buker, George E. Swamp Sailors. Gainesville, Florida: The University Presses of Florida. p. 19, 1975.]

Five days later, on July 23, 1836, a band of Seminole attacked the lighthouse. Thompson and Carter reached the lighthouse tower; Thompson later recounted feeling rifle balls go through his clothes and hat. The Seminoles grabbed the door just after he turned the key to lock it. Thompson exchanged rifle fire with the Seminoles from upper windows in the tower for the rest of the day but after dark, the raiders approached the tower, setting fire to the door and a boarded-up window at ground level. Rifle balls had penetrated tanks in the bottom of the tower, which held 225 gallons of lamp oil for the light, and the oil caught fire. Thompson's clothing had been soaked with oil, and he and Carter retreated to the top of the tower, taking a keg of gunpowder, balls, and a rifle with them. The two men cut away a part of the wooden stairway below them in the tower before being driven out of the top by the searing flames.

The fire flaming up the interior was so bad that Thompson and Carter had to leave the lantern area at the top and lie down on the two foot wide tower platform that ran around the outside of the lantern. Thompson's clothes were burning, and both he and Carter had been wounded by the Seminoles' rifle shots. The lighthouse lens and the glass panes of the lantern shattered from the heat. Sure that he was going to die and wanting a quick end, Thompson threw the gunpowder keg down the inside of the tower. The keg exploded, but did not topple the tower. It dampened the fire briefly, but the flames soon returned as fierce as ever before dying down. Thompson found that Carter had died from his wounds and the fire.

The next day Thompson saw the Seminoles looting and burning the other buildings at the lighthouse station. They apparently thought that Thompson was dead, as they had stopped firing at him. After the Seminoles left, Thompson was trapped at the top of the tower. He had three rifle balls in each foot, and the stairway in the tower had been burned away. Later that day he saw an approaching ship. The United States Navy schooner Motto had heard the explosion of the gunpowder keg from twelve miles away and had come to investigate. The men from the ship were surprised to find Thompson alive. Unable to get him down from the tower, they returned to their ship for the night. The next day the men from the Motto returned, along with men from the schooner Pee Dee. They fired a ramrod tied to a small line up to Thompson, and used it to haul up a rope strong enough to lift two men to the top, who could get the wounded man down. Thompson was taken first to Key West, and then to Charleston, South Carolina, to recover from his wounds.

- Thompson, John W.B. "The Attack on the Lighthouse" (text of a letter from Thompson to the editor of the Charleston Courier), in Drimmer, Frederick. Editor. Captured by the Indians. 1985, Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, pp. 273-276.

The Cape Florida Light was extinguished from 1836 to 1846. [What happened to the body of Aaron Carter? —dff]

Second lighthouse

In 1846 a contract was let to rebuild the lighthouse and the keeper's dwelling. The contractor was permitted to reuse the old bricks from the original tower and house. New bricks were also sent from Massachusetts. The contract went to the low bidder at US$7,995. The lighthouse was completed and re-lit in April, 1847. It was equipped with 17 Argand lamps, each with Template:Convert reflectors.<ref name=inventory/> The new keeper was Reason Duke, who had lived with his family on the Miami River before he moved to Key West because of the Second Seminole War. In Key West his daughter Elizabeth had married James Dubose, son of John Dubose, the first keeper.<ref>Blank 1996, pp. 59-60.</ref>

Temple Pent became the Cape Florida Light keeper in 1852. He was replaced by Robert R. Fletcher in 1854. Charles S. Barron became the keeper in 1855.

1855 renovation

In an 1855 renovation, the tower was raised to 95 feet (29 m), to extend the reach of the light beyond the off-shore reefs. That year the original lamp and lens system was replaced by a second-order Fresnel lens brought to Cape Florida by Lt. Col. George Meade of the United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. The heightened tower with its new, more powerful light, was re-lit in March 1856.<ref>Blank 1996, pp. 79-80, 84.</ref>

Simeon Frow became the keeper in 1859. Confederate sympathizers destroyed the lighthouse lamp and lens in 1861 during the American Civil War. The light was repaired in 1866, and Temple Pent was re-appointed keeper. He was replaced in 1868 by John Frow, son of Simeon Frow.

Decommissioned

John Frow continued as keeper of the Cape Florida Light until 1878, when the light was taken out of service. Even with its height and more powerful lamp and lens, the Cape Florida Light was deemed to be insufficient for warning ships away from the offshore reefs. The US Coast Guard decided to build a screw-pile lighthouse on Fowey Rocks, seven miles (11 km) southeast of Cape Florida.<ref name=uscghist>Template:Cite uscghist</ref> When that was completed 1n 1878, the Cape Florida lighthouse was taken out of service. Keeper John Frow and his father Simeon became the first keepers at the new lighthouse at Fowey Rocks.<ref>Blank 1996, pp. 81-85.</ref>

Inactive period

From 1888 to 1893, the Cape Florida lighthouse was leased by the United States Secretary of the Treasury for a total of US$1.00 (20 cents per annum) to the Biscayne Bay Yacht Club for use as its headquarters. It was listed as the southernmost yacht club in the United States, and the tallest in the world. After the lease expired, the yacht club moved to Coconut Grove.

In 1898, in response to the growing tension with Spain over Cuba, which resulted in the Spanish–American War, the Cape Florida lighthouse was briefly made U.S. Signal Station Number Four. The land around the lighthouse at the end of the 19th century belonged to Waters Davis. His parents had purchased the title to a Spanish land grant for the southern part of Key Biscayne soon after the United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1821. They sold the lighthouse site to the U.S. government in 1825.

In 1913 Davis sold his Key Biscayne property, including the lighthouse, to James Deering, International Harvester heir and owner of Villa Vizcaya in Miami. He stipulated that the Cape Florida lighthouse be restored. When Deering wrote to the U.S. government seeking specifications and guidelines for the lighthouse, government officials were taken aback by the request, wondering how a lighthouse could have passed into private hands. It was soon discovered that an Act of Congress and two Executive Orders, in 1847 and 1897, had reserved the island for the lighthouse and for military purposes. Attorneys eventually convinced the U.S. Congress and President Woodrow Wilson to recognize Deering's ownership of the Cape Florida area of Key Biscayne, including the lighthouse.

Beach erosion threatened to undermine the lighthouse, and records show that a quarter-mile of beach had washed away in front of it in the 90 years since its construction. Deering had engineers inspect the tower to identify needed restoration work. They discovered that the foundations for the tower were only four feet deep. Deering ordered sandbagging at the base of the tower and the construction of jetties to try to stop the erosion. The engineers first proposed driving pilings under the lighthouse to bedrock to support the tower, but soon discovered that there was no hard bedrock. The engineers built a concrete foundation with steel casing for the tower. Subsequent to the installation of the new foundation, the tower survived the eyewall of the 1926 Miami Hurricane.[Blank 1996, pp. 150–151.]

Restoration

The southern third of Key Biscayne, including the lighthouse, was bought by the State of Florida in 1966. It established the land as Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park, named for the editor of the Miami News, who had urged protection and helped arrange the deal for preservation of the land. The state constructed replicas of the keeper's dwellings [FDEP 2001, pg. 27].

In 1978, the Coast Guard restored the lighthouse to active service, one hundred years after it was decommissioned. An automated light was installed in the tower to serve as a navigational aide. A lighthouse inspection in 1988 found that the foundation installed during Deering's time was in excellent condition. After twelve years of service, the light was decommissioned by the Coast Guard in 1990. The tower survived the close passage of Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

As part of a 1995–6 renovation, the light was replaced with its present optics before its reactivation. The lighthouse was relit in time for the Miami Centennial celebration in July 1996. "Cape Florida Light" It is now owned and managed by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

In 2004 a sign was installed in the park to commemorate the site for the escape of hundreds of slaves and Black Seminoles to the Bahamas in the nineteenth century. It is part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Trail."Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park", Network to Freedom.

Depictions in popular media

- Popular Science published a picture of the Cape Florida lighthouse in 1930, claiming that the lighthouse was over 200 years old, and still in use. Some bathing beauties were apparently composited into the picture. [Lighthouses of Strange Designs, Popular Science, 1931]

- As a Miami landmark, the lighthouse was featured in several episodes of the television series Miami Vice, most extensively during the two-part episode "Mirror Image" (first aired May 6, 1988).

- It was featured briefly at the end of the 1945 John Wayne film They Were Expendable (1945), and as the backdrop of a grisly murder in the Kurt Russell thriller The Mean Season (1985).

- The lighthouse was featured in the third TV season of Burn Notice, in episode 14 entitled, "Partners in Crime" (first aired February 18, 2010).

Charles M. Brookfield Cape Florida Light

Along the southeast Florida coast no more cheery or pleasing sight gladdened the heart of the passing mariner of 1826 than the new lighthouse and little dwelling at Cape Florida. Beyond the glistening beach of Key Biscayne the white tower rose sixty-five feet against a bright green backdrop of luxuriant tropical foliage. Who could foresee that this peaceful scene would be the setting for events of violence, suffering and tragedy?

At night the tower's gleaming white eye followed the mariner as he passed the dangerous Florida Reef, keeping watch to the limit of its visibility. When in distress or seeking shelter from violent gales the light's friendly eye guided him into Cape Florida Channel to safe anchorage in the lee of Key Biscayne. From the beginning of navigation in the New World, vessels had entered the Cape channel to find water and wood on the nearby main. Menendez in 1567 must have passed within the Cape when he brought the first Jesuit missionary, Brother Villareal, to Biscayne Bay.

Two centuries later, during the English occupation, Bernard Romans, assistant to His Majesty's Surveyor General, in recommending "stations for cruisers within the Florida Reef", wrote:

"The first of these is at Cayo Biscayno, in lat. 250 35' N. Here we enter within the reef, from the northward... you will not find less than three fathoms anywhere within till you come abreast the south end of the Key where there is a small bank of 11 feet only, give the key a good birth, for there is a large flat stretching from it. At the south end of the Key very good water is obtainable by digging... at the watering place on the key is also an excellent place for careening of vessels, not exceeding 10 feet draught. All these advantageous circumstances... make this an excellent place for cruizers to watch every vessel bound northward. In the year 1773, I came a passage from Mississippi, on board the schooner Liberty, commanded by Capt. John Hunt. We had the misfortune to be overset at sea, and I conducted the wreck into this place, when having lost our boats and caboose, with every other thing from off the deck, we nailed together three half hogsheads, in which a man and a boy went ashore... "At this place there is a vast abundance and variety of fish, both in creeks and outside at sea, particularly groopers are in great plenty, king-fish, Spanish mackerel and Barrows are also often caught towing; and if you have one or two good hunters aboard, you may always be provided with plenty of venison, turkies and bear meat. There are... deer on the key and sometimes bear; in winter duck and teal abound in the creeks; turtle is very plenty;... no fish is poisonous on the Florida shore, not even the amber-fish; but on the Bahama side, precaution is necessary; and the loggerhead turtle is never rank of taste here."

But neither the religious Spaniard nor the aggressive Briton left any trace of his former presence on Florida's southeast coast. It remained for the New World's "Infant Republic" to erect the first substantial structure. The Congress of the United States on May 7, 1822 appropriated $8,000 for building a lighthouse on Cape Florida. In April, 1824 an additional $16,000 was added by Congress for the same purpose. Collector Dearborn, of Boston contracted with Samuel B. Lincoln "for a tower sixty-five feet high with solid walls of brick, five feet thick at the base, graduated to two feet at the top." Noah Humphreys, of Hingham, was appointed to oversee the materials and work. He certified the lighthouse and dwellings as finished according to contract December 17, 1825. The three acre site deeded by Mr. Waters S. Davis, Sr. was a gift to the government.

For more than ten years the faithful keepers of the light lived, with their families, a lonely but peaceful life at the Cape punctuated by periodic cruises to Key West, their only contact with civilization. But in 1835 the outbreak of the Second Seminole War brought terror to the scattered settlers of the southeast coast. The Cooley (one source has it "Colee") family on the north side of New River were the first to be massacred. Two families on the south side of the river escaped southward spreading the alarm to the mouth of the Miami River, where William English, of South Carolina, employed about twenty-five hands on his farm. R. Duke, with his family, lived about three miles up the river. His son, Capt. John H. Duke, survived the Indian attack and recorded the details:

"After midnight in December 1836, we were called up by two negro men from the farm below, giving the alarm that the Indians were massacreing the people in the neighborhood. Everybody left their homes in boats and canoes for the Biscayne (Cape Florida) light-house. On arrival there a guard was formed and kept until vessels could be obtained to carry th families to Key West. Two men, one white by the name of Thompson, one colored, name I don't know, volunteered to keep the light going until assistance could be sent there."

Thompson's Firsthand account

These two heroes, one white, the other a nameless, aged negro, did not have long to wait-the first for indescribable suffering and torture, the second for death. This story is best told by assistant keeper John W.B. Thompson, himself, in a letter:

"On the twenty-third of July, 1836, about 4 P.M., as I was going from the kitchen to the dwelling house, I discovered a large body of Indians within twenty yards of me, back of the kitchen. I ran for the Lighthouse, and called out to the old negro man that was with me to run, for the Indians were near. At that moment they discharged a volley of rifle balls, which cut my clothes and hat and perforated the door in many places. We got in, and as I was turning the key the savages had hold of the door. I stationed the negro at the door, with orders to let me know if they attempted to break in. I then took my three muskets, which were loaded with ball and buckshot, and went to the second window. Seeing a large body of them opposite the dwelling house, I discharged my muskets in succession among them, which put them in some confusion; they then, for the second time, began their horrid yells, and in a minute no sash of glass was left at the window, for they vented their rage at that spot. I fired at them from some of the other windows, and from the top of the house; in fact, I fired whenever I could get an Indian for a mark. I kept them from the house until dark.

They then poured in a heavy fire at all the windows and lantern; that was the time they set fire to the door and window even with the ground. The window was boarded up with plank and filled with stone inside; but the flames spread fast, being fed with yellow pine wood. Their balls had perforated the tin tanks of oil, consisting of two hundred and twenty-five gallons. My bedding, clothing, and in fact everything I had was soaked in oil. I stopped at the door until driven away by the flames.

"I then took a keg of gunpowder, my balls and one musket to the top of the house, then went below and began to cut away the stairs about halfway up from the bottom. I had difficulty in getting the old negro up the space I had already cut; but the flames now drove me from my labor, and I retreated to the top of the house. I covered over the scuttle that leads to the lantern, which kept the fire from me for sometime. At last the awful moment arrived; the cracking flames burst around me.

"The savages at the same time began their hellish yells. My poor negro looked at me with tears in his eyes, but he could not speak. We went out of the lantern and down on the edge of the platform, two feet wide. The lantern was now full of flame, the lamps and glasses bursting and flying in all directions, my clothes on fire, and to move from the place where I was would be instant death from their rifles. My flesh was roasting, and to put an end to my horrible suffering I got up and threw the keg of gunpowder down the scuttle-instantly it exploded and shook the tower from top to bottom. It had not the desired effect of blowing me into eternity, but it threw down the stairs and all the woodenwork near the top of the house; it damped the fire for a moment, but it soon blazed as fierce as ever.

The negro man said he was wounded, which was the last word he spoke. By this time I had received some wounds myself; and finding no chance for my life, for I was roasting alive, I took the determination to jump off. I got up, went inside the iron railing, recommending my soul to God, and was on the point of going ahead foremost on the rock below when something dictated to me to return and lie down again. I did so, and in two minutes the fire fell to the bottom of the house. It is a remarkable circumstance that not one ball struck me when I stood up outside the railing although they were flying all around me like hailstones. I found the old negro man dead, being shot in several places, and literally roasted. A few minutes after the fire fell a stiff breeze sprung up from the southward, which was a great blessing to me. I had to lie where I was, for I could not walk, having received six rifle balls, three in each foot.

"The Indians, thinking me dead, left the lighthouse and set fire to the dwelling place, kitchen and other outhouses, and began to carry off their plunder to the beach. They took all the empty barrels, the drawers of the bureaus, and in fact everything that would act as a vessel to hold anything. My provisions were in the lighthouse, except a barrel of flour, which they took off.

The next morning they hauled out of the lighthouse, by means of a pole, the tin that composed the oil tanks, no doubt to make grates to manufacture the coonty root into what we call arrow root. After loading my little sloop, about 10 or 12 went into her; the rest took to the beach to meet at the other end of the island. This happened, as I judge, about 2:00 a.m.

My eyes, being much affected, prevented me from knowing their actual force, but I judge there were from 40 to 50, perhaps more. I was now almost as bad off as before; a burning fever on me, my feet shot to pieces, no clothes to cover me, nothing to eat or drink, a hot sun overhead, a dead man by my side, no friend near or any to expect, and placed between 70 and 80 feet from the earth and no chance of getting down. My situation was truly horrible.

About 12 o'clock I thought I could perceive a vessel not far off. I took a piece of the old negro's trousers that had escaped the flames by being wet with blood and made a signal. Some time in the afternoon I saw two boats with my sloop in tow coming to the landing. I had no doubt but they were Indians, having seen my signal; but it proved to be the boats of the United States schooner Motto, Captain Armstrong, with a detachment of seamen and marines under the command of Lieutenant Lloyd, of the sloop-of-war Concord. They had retaken my sloop, after the Indians had stripped her of her sails and rigging, and everything of consequence belonging to her.

"They informed me they heard my explosion 12 miles off, and ran down to my assistance, but did not expect to find me alive. These gentlemen did all in their power to relieve me, but, night coming on, they returned on board the Motto, after assuring me of their assistance in the morning. Next morning, Monday, July 5, three boats landed, among them Captain Cole, of the schooner Pee Dee, from New York.

They made a kite during the night to get a line to me, but without effect, they then fired twine from their muskets, made fast to a ramrod, which I received, and hauled up a tailblock and made fast round an iron stanchion, rove the twine through the block, and they below, by that means, rove a two-inch rope and hoisted up two men, who soon landed me on terra firma.

I must state here that the Indians had made a ladder by lashing pieces of wood across the lightning rod, near 40 feet from the ground, as if to have my scalp, nolens volens. This happened on the fourth. After I got on board the Motto every man from the captain to the cook tried to alleviate my sufferings.

On the seventh I was received in the military hospital, through the politeness of Lieutenant Alvord of the fourth Regiment of United States Infantry. He has done everything to make my situation as comfortable as possible. I must not omit here to return my thanks to the citizens of Key West, generally, for their sympathy and kind offers of anything I would wish that it was in their power to bestow. Before I left Key West two balls were extracted, and one remains in my right leg, but since I am under the care of Dr. Ramsey, who has paid every attention to me, he will know best whether to extract it or not. These lines are written to let my friends know that I am still in the land of living,

and am now in Charleston, S.C., where every attention is paid me. Although a cripple, I can eat my allowance and walk without the use of a cane."

Skullduggery and collusion were brought to light by the partial destruction of the light-house. When the collector at Key West visited Cape Florida after the Indian attack, he found the walls of the tower to be hollow from the base upwards instead of solid as called for in the contract. Apparently no charges were placed against those responsible.

The destruction of the light was a great handicap to the rapidly growing commerce of the young Republic. Soon, too soon, the government attempted reconstruction and repair. General Jesup having accepted the surrender of most of the Seminole Chiefs, the war was believed to be at an end. Accordingly, under date of June 20, 1837, Winslow Lewis, of Boston, received a letter from Mr. Pleasonton, the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, inquiring "on what terms and within what period, he would undertake to repair or rebuild the light-house at Cape Florida; suggesting at the same time, that the interest of commerce and navigation required the work to be done as speedily as possible." Lewis's terms were accepted within ten days of the inquiry "in consideration of the importance to navigation of having the lighthouse lighted in the shortest time." In July a fully equipped vessel sailed from Boston. Aboard were a superintendent, all necessary workmen and materials. Touching at Key West, the vessel took on board Mr. Dubose, keeper of the former light, who was to superintend repairs for the Government, and take charge upon completion. While at Key West Deputy Collector Gordon advised Lewis's agent that in his opinion the lighthouse could not be repaired at this time due to the resumption of hostilities by the Indians; that even if the workmen succeeded in their undertaking the Indians would destroy the building immediately. But, nevertheless, the vessel proceeded to Cape Florida only to find "that hostile Indians were in entire possession of the adjacent country" and had recently murdered Captain Walton, Commander of the light vessel at Carysfort Reef. Dubose protested against any attempt to begin work and declared he would not remain as keeper if the lighthouse were repaired but would leave with the workmen. Faced with this situation, Knowlton, Lewis' agent, believed it to the advantage of the Government to abandon the attempt at repairs. He returned with the vessel to Boston. Lewis presented a claim for expenses to Congress. The Committee of Claims considered his account, totaling $1,781.68, not extravagant, and recommended the introduction of a bill to reimburse him. In the Report, the Committee observed: "It is evident that the loss of the claimant was occasioned by his laudable alacrity in attempting to execute the contract on his part. Had he been less prompt... the resumption of hostilities by the savages would have been known at Boston before the sailing of the vessel, and the loss which he sustained consequently avoided."

From 1838 to 1842 the war scarred light tower at Cape Florida was an important landmark and rendezvous for the nine vessels of the U.S. Navy's Florida Squadron. Under John T. McLaughlin, Lieut. Com'g., the Squadron included the "Campbell" and "Otsego" of the Revenue Cutter Service, now the U. S. Coast Guard. Attached to this force were 140 canoes used for expenditions into the Everglades. Among officers of the Squadron who took part in the Okeechobee Expedition, was Passed Midshipman George H. Preble, later Rear Admiral Preble of Civil War fame. Marines from the Squadron garrisoned Fort Dallas on the Miami River across the Bay.

At the Cape itself, Lieut. Col. William S. Harney based his 2nd Dragoons, the famous 2nd Cavalry. Here Harney organized his successful Everglades Expedition that destroyed the power of Chief Chekika, dreaded leader of the Caloosahatchee and Indian Key massacres.

Congress had appropriated $10,000 by March 3, 1837, and included $13,000 more August 10, 1846, to rebuild the lighthouse tower. The work was finally completed and the light in operation in 1846. R. Duke was appointed keeper. But marine architects were now designing faster ships-clippers carrying a great press of sail, and of deeper draught. It was necessary, for their safe navigation, to lay a course at a greater distance to clear the shoals of the Florida Reef. Aids to navigation must be seen from further off shore. In 1855 the old light tower was elevated and "fitted with the most approved illuminating apparatus." This is the present tower-95 feet from the base to the center of the lantern.

Destroyed in 1861, the lighting apparatus was replaced and in operation in 1867. At the completion of the steel light on Fowey Rock, historic Cape Florida Light was discontinued June 16, 1878. The friendly, guiding eye gleamed no more. The tower and property were sold in 1915 to Mr. James Deering of Chicago, Illinois.

Sources

- Blank, Joan Gill, Key Biscayne. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. Template:ISBN.

- Love Dean, Lighthouses of the Florida Keys, Pineapple Press, 1998.

- Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) (2001-03-15). "Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park Unit Management Plan".

- "Inventory of Historic Light Stations - Florida Lighthouses - Cape Florida Light". National Park Service. Retrieved on 2012-11-15.

- Light List, Volume III, Atlantic Coast, Little River, South Carolina to Econfina River, Florida (PDF). Light List. United States Coast Guard. 2010, p. 8.

- Cape Florida The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 29 June 2016

- Florida Historic Light Station Information & Photography United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 29 June 2016

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Florida". CORIS, NOOA's Coral Reef Information System. Retrieved on 2012-11-26.

- Good photo here.

- Buker, George E. 1975. Swamp Sailors. Gainesville, Florida: The University Presses of Florida. pg. 19.

- Thompson, John W.B. "The Attack on the Lighthouse" (text of a letter from Thompson to the editor of the Charleston Courier), in Drimmer, Frederick. Editor. 1985. Captured by the Indians. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, pp. 273-276.

- "Historic Light Station Information and Photography: Florida". United States Coast Guard Historian's Office. Archived from the original on 2017-05-01. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- "Cape Florida Light" Archived October 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Lighthouse Friends. Retrieved on 2012-11-15.

- "Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park", Network to Freedom, National Park Service, 2010, accessed 10 April 2013.

- "Lighthouses of Strange Designs." Popular Science. Google books, retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Romans, Bernard, A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida, etc. New York, 1775.

- House of Representatives-Act approved May 7, 1822.

- House of Representatives--Act Approved April 2, 1824.

- House of Representatives-Act of March 10, 1837.

- House of Representatives-Report No. 373-25th Congress, Second Session, 12 January, 1838.

- Records Public Information Division, U.S. Coast Guard, Washington, D.C.

- Hollingsworth, Tracy, History of Dade County, Miami, 1936.

- McNicoll, Robert E. "The Caloosa Village Tequesta," Tequesta, Journal of Historical Association of Southern Florida, March, 1941.

- Duke, John H. (Statement) Pensacola, Dec. 27, 1891 (from U.S.C.G. records).

- Munroe and Gilpin, "The Commodore's Story," New York, 1930.

- Sprague, John T. Origin, Progress and Conclusion of the Florida War, New York, 1848.

- Rodenbough, Theo. F., "From Everglade to Canyon," New York, 1875.

- Griswold, Oliver, Wm. Selby Harney, Indian Fighter. Paper presented at Annual Meeting, Florida Historical Society, Miami, April 9, 1949.

- The Weekly Wisconsin Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 20 Aug 1851, Wednesday, p. 4.

- The Miami News Miami, Florida, 9 February, 1922, Thu, p. 12

External links

- https://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=360

- Cape Florida Light - National Park Service Inventory of Historic Light Stations

- Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park

- Title Niles' Weekly Register, Volume 51, Baltimore, 1837. Original from the New York Public Library

- https://www.flkeysnews.com/living/article147339204.html

- A dramatic account of the battle by Elinor DeWire, 2018.

- https://www.facebook.com/atropicalfrontier/posts/thompson-john-w-b-biscayne-bay-cape-florida-called-irwin-thompson-by-nathan-shap/2564877170283736/