John Andre

Contents

New England Historical Society

http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/spy-spy-john-andre-hanged/

A Spy for a Spy: John Andre Hanged

On Oct. 2, 1780, British intelligence officer John Andre met his awful fate with courage, much as his American counterpart Nathan Hale met his four years earlier. For Andre died on the gallows as a spy, though he probably would have avoided that fate had the British spared Hale. John Andre conspired with Continental Army Brigadier General Benedict Arnold to surrender the fort at West Point to the British. Arnold, recently appointed commandant at the fort, turned traitor because of greed and resentment. The British offered to pay him 20,000 pounds for the deed, more than $1 million today.

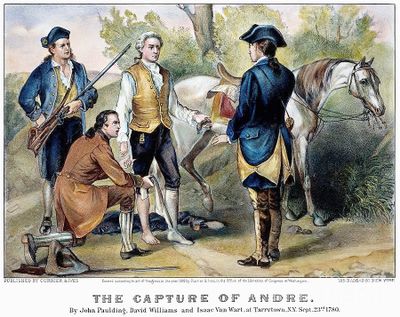

American militiamen captured 30-year-old John Andre on his way to New York City. A wealthy, London-born Huguenot, he had served 10 years in the 7th Royal Fusiliers. The Americans had captured him once before, at Fort Saint-Jean in Quebec, and held him in Lancaster, Pa.

After he gave his word that he wouldn’t try to escape, he could roam the Pennsylvania town freely. He returned to duty after his exchange for an American prisoner in 1776.

A Good Singer

John Andre joined the British occupations of New York and Philadelphia, where he lived in Benjamin Franklin’s house. He was a favorite among colonial society as he was a charming conversationalist, a good singer and a talented artist. In Philadelphia he had become friendly – and possibly more than friendly – with Peggy Shippen, a Loyalist. She later married Benedict Arnold and acted as their go-between.

In late September 1780, John Andre left his sloop-of-war anchored in the Hudson River and met Arnold on land. The next day, American troops fired on the ship, forcing it to move downriver. The ship's departure left Andre stranded.

Arnold gave him civilian clothes, a fake passport and six papers showing the British how to take West Point. Andre hid the papers in his boot.

American militiamen captured him in Tarrytown, N.Y., and discovered the incriminating papers in his boot. Gen. George Washington then named a board of officers to hear his case. The board found him guilty of spying and sentenced him to death.

John Andre, Doomed

In the case of Hale, the colonists took great umbrage to his execution as a spy by hanging. They argued that he acted in a military capacity and deserved better treatment. The customs of the time allowed no wiggle room, however. As he didn't wear a uniform when captured, the British gave him a spy’s sendoff.

As a result, the Americans viewed any consideration for John Andre as out of the question.

Dr. James Thacher, a Continental Army surgeon, gave an eyewitness account of Andre’s last day in his memoir, The American revolution, from the commencement to the disbanding of the American army : given in the form of a daily journal, with the exact dates of all the important events; also a biographical sketch of all the most prominent generals

A Momentary Pang

“So soon, however, as he perceived that things were in readiness, he stepped quickly into the wagon, and at this moment he appeared to shrink, but instantly elevating his head with firmness he said, "It will be but a momentary pang," and taking from his pocket two white handkerchiefs, the provost-marshal, with one, loosely pinioned his arms, and with the other, the victim, after taking off his hat and stock, bandaged his own eyes with perfect firmness, which melted the hearts and moistened the cheeks, not only of his servant, but of the throng of spectators.

"The rope being appended to the gallows, he slipped the noose over his head and adjusted it to his neck, without the assistance of the awkward executioner.

"Colonel Scammel now informed him that he had an opportunity to speak, if he desired it; he raised the handkerchief from his eyes, and said, "I pray you to bear me witness that I meet my fate like a brave man." The wagon being now removed from under him, he was suspended, and instantly expired; it proved indeed "but a momentary pang."

"He was dressed in his royal regimentals and boots, and his remains, in the same dress, were placed in an ordinary coffin, and interred at the foot of the gallows; and the spot was consecrated by the tears of thousands ...”[optinrev-inline-optin2]

This story about John Andre was updated in 2019. You may also want to read about Alexander Scammell, the lovesick Revolutionary War hero appointed as John Andre's executioner here.

RELATED ITEMS:AMERICAN, AMERICAN REVOLUTION, BENEDICT ARNOLD, BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, COLONISTS, CONGRESS, CONNECTICUT, CURRIER & IVES, GEORGE WASHINGTON, LIBRARY, LOYALIST, MILITARY, NORWICH, REVOLUTION, REVOLUTIONARY WAR, SIX, SPYING, WAR, YORK

U.S. History

http://www.ushistory.org/march/bio/andre.htm

Major John Andre. John Andre--handsome, artistic, beloved by the Loyalists, admired by Washington ... a spy brave and cunning ... convinced Benedict Arnold to sell out West Point ... hanged at age 31.

John Andre was born in London in 1750 to French Protestant (Huguenot) parents. His father was a merchant, born in Geneva, Switzerland; his mother was born in France and moved to England when she was young. He attended school in Geneva, returning to London in 1767, two years before his father died.

The young Andre was a charismatic and charming man whose manners and advanced education set him apart from his contemporaries in England. He was fluent in English, French, German, and Italian. He drew and painted, wrote lyric and comic verse, and played the flute.

The glamour of military life appealed to Andre, but coming from the merchant class and of limited means, he would not be able to advance in the British army, where a purchase system almost always governed promotions.

After his father's death, in 1769, Andre felt obliged to financially care for his family and entered his father's counting house.

That same year, Honora Sneyd declared her love for him -- all he had to do to obtain her guardian's approval and win her hand in marriage was to grow rich. Andre strove to succeed, but before too long Honora found that her feelings for him had cooled. Andre decided now to follow his dream and join the army.

Driven by a Broken Heart Anna Seward, the English poet and foster sister of Honora, asserted that Andre was driven to join the army by a broken heart. Thus, he was commissioned on March 4th, 1771, and selected for special training in Germany, where he spent two years. In 1774 he went to America as lieutenant in the Royal English Fusileers traveling to Canada by way of Philadelphia and Boston.

As a British lieutenant in Canada, Andre was involved in the defense of St. Johns which was taken by American forces on November 2, 1775, after a two-month siege.

He became a prisoner of war and was transferred to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. It was not uncommon for officers who were prisoners of war to be entertained en route to their places of detention, and Andre had dinner in Haverstraw, New York, at the home of a Mr. Hays. Also present was Mr. Hays's brother-in-law, Joshua Hett Smith. Five years afterwards, Andre and Smith would meet again, apparently without recognition on either side; in 1780 it was Joshua Hett Smith who set Andre on the road to capture and death.

In Lancaster, the enlisted prisoners were kept in barracks, while captured officers were housed at their own expense in local inns. Andre was among those officers allowed to reside with a local family. He moved in with the Caleb Cope family. The Copes developed a real affection for Andre, who gave art lessons to their eldest son. Further, in this German-speaking Lancaster community, Andre's fluency added to his popularity.

At the close of 1776, as part of a prisoner exchange, Andre was returned to Howe, now wintering in New York. Andre presented Howe a memoir he had compiled from his observations in "the colonies." Impressed by the young man's abilities, Howe first gave him a captaincy in the 26th Regiment and recommended him as an aide to Major-General Charles Grey.

In August, 1777, serving under Grey, Andre was among the 17,000 British who landed at Head of Elk, Maryland, which led to the occupation of Philadelphia. Andre was present at the Battle of Brandywine, Grey's bloody night raid, known as the Paoli Massacre, the Battle of Germantown, the British occupation of Philadelphia, the Battle of Monmouth, and Grey's brutal raids of 1778 in Massachusetts and New Jersey. One of the most reliable sources for the history of the war from the British side is Andre's Journal.

During the Winter 1777–78 British occupation of Philadelphia, while Washington endured at Valley Forge, Andre wrote poetry for the Tory women, including Peggy Shippen, and took center stage in making the otherwise boring days entertaining. He planned the notorious Mischianza extravaganza of May 18, 1778, in honor of Howe's impending departure.

Looting Benjamin Franklin's House

During his nearly nine months in Philadelphia, Andre lived in Benjamin Franklin's house. While the British were preparing to evacuate the city, Andre shocked his friend Du Simitiere (a Swiss-born citizen of Philadelphia) by looting Franklin's house. Arriving to say good-bye, Du Simitiere found the young officer -- known for his courtesy -- packing books, musical instruments, scientific apparatus, and a portrait of Franklin. Andre did not respond to Du Simitiere's protests. Long afterwards, the portrait of Franklin was returned to the America by the descendants of General Grey, and today it hangs in the White House. It now seems clear that Andre looted Franklin's house under orders from Grey, explaining Andre's inability to offer his friend an explanation.

Following Grey's departure, in November 1778, Andre was awarded the rank of major and appointed deputy Adjutant General on the the staff of Sir Henry Clinton, Howe's successor and the new British Commander in Chief.

General Clinton was solitary, resentful, and stubborn, and yet Andre was successful in gaining a friendship and even fondness. Clinton had confidence in Andre's resourcefulness and discretion, and he delegated to Andre the coordination of British intelligence activities. He entered enthusiastically into his new responsibilities. His journal sheds light on his competance maintaining secrecy among his network of spies, while gathering information as to which American officers might prove corruptible.

In 1778-79, Clinton's army wintered in New York (1778-79) and lost precious time waiting for reinforcements who didn't arrive until August.

On May 10, 1779, Andre received a most historic offer. American General Benedict Arnold, commander of West Point, the fort key to control of the Hudson Valley and New England, offered to surrender the fort to the English -- for a fee. Negotiations continued for months, but bogged down over the fee. Arnold wanted 10,000 pounds, success or failure. Clinton demanded success.

In 1779, Clinton's forces headed down to Savannah to meet the French flottila commanded by Admiral d'Estaing, where Clinton's forces easily prevailed and returned to New York.

On December 26, 1779, Andre was with Clinton for a successful amphibious assault on Charleston leading to a May 12 surrender.

On or about May 1780, Arnold reinitiated his contact with Andre, informing him that the Rochambeau's French force was on its way to Newport, Rhode Island. In response, Clinton broke off his Southern campaign, left Cornwallis in charge and returned to New York to prepare for the French assault.

Now, Benedict Arnold arranged to be made Commandant at West Point. On July 15, Arnold asked for 20,000 pounds in return for successfully ceding West Point to the enemy. Referring to Andre, Arnold wrote to Clinton, "A personal interview with an officer that you can confide in is absolutely necessary to plan matters." This arrangement was accepted.

Benedict Arnold Gives Up the Fort On the night of September 21, Andre came ashore from the British sloop "Vulture," anchored in the Hudson just south of West Point, met with Arnold, accepted a sheaf of documents, and spent the night at the house of Joshua Hett Smith -- the man Andre broke bread with in New York, years earlier -- some miles within the American lines.

During the night, the "Vulture" was bombarded from the shore by American artillery, and withdrew down the river.

Smith, a Loyalist collaborator, escorted Andre back to the "Vulture," only to find it missing. To their consternation, they recognized that they'd need to cross overland through American-held territory.

Andre Dresses for the Trip Because wearing his British uniform was too dangerous, Andre donned an American uniform for the treacherous trip. Smith accompanied Andre all but the last 15 miles, which were through British territory. It was in that last distance, while traveling alone and believing himself out of danger that Andre was stopped by a trio of American freelancers, dressed in British uniform. Andre commanded them to give way. They revealed themselves and searched Andre, discovering Arnold's papers hidden in his boot, and arrested Andre for espionage.

The Treachery Is Exposed

It was assumed that Andre possessed stolen papers. What followed was a sequence of improbable coincidences and near-misses that led to the recognition that Arnold was a traitor and to his escape. Arnold learned that his treason was discovered and escaped downriver to the "Vulture" at the same time that Washington was arriving unexpectedly at West Point -- and all on the very day that the fortress was to have been surrendered to the British.

Andre was imprisoned at Tappan, New York, and on September 29, 1780, he was found guilty of being behind American lines "under a feigned name and in a disguised habit." Andre was hanged as a spy at noon on October 2, 1780.