History of the Museum

Contents

- 1 Lena's Lunch

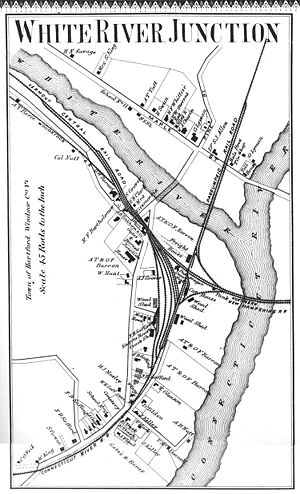

- 2 White River Junction

- 3 Art at the Original Museum

- 4 Hartford Village

- 5 The Tunbridge Fairgrounds, Site of the Vermont History Expo

- 6 Selections from the Main Street Museum Collection at the Fleming Museum, Burlington

- 7 The Former Fire Station Building and Restoration of the Museum to downtown White River Junction

- 8 Dartmouth Regional Selections Show

- 9 A Display Case with a View; Notes From the Desk of a Small Museum

- 10 Primary Sources

Lena's Lunch

"The past is never dead. It's not even past." —Faulkner

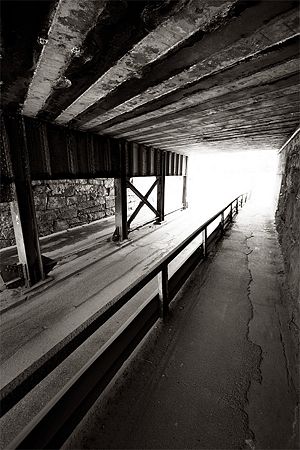

The Lena's Lunch Building in downtown White River Junction featured a "faux-brick" front and had a very funky smell when i first walked through its aluminum doors in 1992. It was a long, narrow, shot-gun retail space. There was a pile of garbage in the middle of the room. The sink had been used to mix cement in. In the 1930's it had been a bowling alley. There were feral cats roaming the place, and spraying. It was just perfect.

White River Junction

White River Junction seemed like a small town with big city problems.

Neighbors were overly friendly, seemed to have lived there forever and liked to sit on the front stoop of the Lena's Lunch Building and hang out in a general way on the sidewalk on my block. They had worked on the railroad in its hay-day, in restaurant or hotel service, or did a little of anything that came their way and became nomadic when hard times made the rent impossible to make. Some were older and on disability like Tony Vitigliani. Tony walked over from the next door apartment and sat on the front step of the Museum every day. As a boy he had worked setting up the pins at the bowling alley. "You'd have to watch out for the drunks", hed say. They would lob bowling balls down the lane while the kid was setting up the pins. This was either intentional, or just because they were drunk.

The Museum was settling into a building that had been a bowling alley with a dance hall upstairs. The dance hall was called the Winter Gardens and served booze during the Prohibition years. Most of South Main Street had been a haven for illegal booze during the 1920s. There was a "garage" further South on the Street with a rolling wall. Roll the rack of tools to one side, and there were shelves of Canadian liquor awaiting thirsty customers.

The Winter Gardens had been a gambling palace, complete with one armed bandits" in the Prohibition years. Tony told me that one disappointed patron had actually thrown the slot threw a window, and that he and neighborhood rug rats had scooped up quarters from the alleyway.

Art at the Original Museum

"If history were told in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten." —Rudyard Kipling.

It was an accident. I think there were two reasons for the museum formation. The first was my grandmother, Elizabeth Gillingham, who gave me things, even when i was very small; the second is the storefront I inhabited on South Main Street, across from the Legion Hall.

Schedule for the (first) Main Street Museum Of Art (exhibits included many other artists not listed in formal invitations or pr, to each of them we extend our gratitude, especially to Mr. Chip Hopkins):

- December, 1992:

- First Open House and Ecumenical Holiday Observance.

- 1993:

- Special hand colored photographs and “Gagaritypes” in a Ponderous Display by Slugo Manashevitz Gagarin, a local disenfranchised person.

- Paintings of Steven Dunning—Vibrant, Pop-focused, Sexual Send-Offs. Back Room exhibit of Richard Coles, self-taught local artists acrylic and oil paintings with Nazi motifs.

- 1994:

- Social Realist works on gessoed paper in pen, wash and varnish by David Fairbanks Ford,

- All Elvis Art Show, over a dozen “Wannabes” from all walks of life and all parts of the country exhibiting gold records, paintings, sculputure, photos, assemblagés, and Love, with Elvis himself, returned from the dead, performing Live in a Free Concert.

- Annual Holiday Entertainment initiated featuring a Virgin, a shepherd named Joseph, a Christ Child and all the animals in a manger—Puppets by Ria Blaas.

- 1995:

- Nat Hemenway, “Art Brut,” in painting/sculpture/photo concoctions from Tunbridge, Vermont.

- Sea Monster, vile creature dredged from the waters of the Connecticut River; baffled scientific experts at nearby Dartmouth College and exhibited for a very reasonable price—25 Cents A Person.

- Dennis Grady, assemblages shipped directly to the Museum from the Galleries of the University of Ohio at Athens.

- 1996:

- Large scale works on paper, conte, pencil and oil-stick by Lisa Kippen.

- Summer Puppet Shows by Ria Blaas in addition to her Annual Holiday Cheer.

- Jack Rowell, "Big Fish and Good Lookin' Women", photos of the Flip Side of Vermont, the Tunbridge Fair, biker buddies, wild parties, violence and Fred Tuttle.

- September, 1996:

- Inspectors from Vermont Dept. of Labor and Industry—a one day visit (and numerous return trips.) "Zero" persons allowed to occupy the public space of the Building.

Hartford Village

The center of Hartford Village is a picturesque spot for a Museum.

The Tunbridge Fairgrounds, Site of the Vermont History Expo

The Vermont Historical Society sponsors a yearly Expo on the grounds of the great World's Fair.

Selections from the Main Street Museum Collection at the Fleming Museum, Burlington

Re/Collections, 2000, c.e. Robert Hull Fleming Museum, Burlington, Vermont.

The very first conversations concerning the nature of this exhibit concerned organization and re-organization. General conclusions were formed on the nature of the show, what other collections were to be included, exhibition. Other important concerns dear to curators hearts were batted about.

It was also ascertained that there is no cognative difference between “organization” and “re-organization” at least within the museum curating world. “There is nothing new under the sun,” and this truism applies most aptly in storage and “deep storage” in any of the world’s museums. In a world obsessed with novelty, this is considered a liability. And yet, it is the familiarity of these objects and the comfortable manner in which the curators have presented them that makes “Re/Collections” so congenial, and so accessible to audiences’ hearts and minds. As children we dug up old toys or strange pieces of machinery, whose use was long forgotten. We may have found, buried deep within the back of an elderly relative’s chest of drawers, a cache of costume jewelry, old letters, and other mashed-together offerings—usually held together with decomposing rubber-bands. Most human lives add up to this in the end and we will all probably be remembered by small poignant things stashed away in boxes, under beds and even in the partitions of walls.

Squirrels hoard butternuts in wood-piles and stone-walls. Humans hoard old shoes and old grocery lists in similar places, but usually indoors. (Hence the verb, “squirreling away”.) It is in the spirit of this re-organization that Re/Collections features rarely glimpsed curiosities from the Robert Hull Fleming Museum’s vast and varied holdings combined with illuminating counterpoints in the form of selections from Vermont’s Main Street Museum in White River Junction, as well as culturally significant contemporary artifacts procured locally at second-hand stores.

These artifacts, though once deemed important enough to classify, number and accession, perhaps have fallen out of favor with current curatorial practice, or, simply have been stored, unexamined, for decades. The objects of more recent provenance, culled from local second-hand merchants, further point to society’s ongoing selectivity with regard to its material culture. In their current setting, they are imbued with a sense of wonder—that almost forgotten fomentation—and honored, as valued knickknacks should be, in jewel-like settings.

Re/Collections is co-curated by three talented colleagues: the director of The Main Street Museum, David Fairbanks Ford, Fleming Museum curator Janie Cohen, and Firehouse Center for the Arts curator Pascal Spengemann.

The Fleming's collections are awash in the remarkable, the ignored, and the formerly significant. The Main Street Museum is renown for its own remarkable trove of astonishing items of both natural-historical and aesthetic interest. These two collections, combined with carefully chosen artifacts from Vermont’s thrift stores, set out to plumb the depths of the very idea of the museum and curating. The exhibition strategies utilized here harken back to the inclusiveness of the Fleming’s formative years. Juxtapositions of objects previously unconnected can produce an electrifying tableau—the resultant combination exceeding the sum of its parts. So, too, the cohesion of the collections and perspectives of the Fleming Museum, the Main Street Museum and significant second-hand store presentations.

The Former Fire Station Building and Restoration of the Museum to downtown White River Junction

Dartmouth Regional Selections Show

2003.

A Display Case with a View; Notes From the Desk of a Small Museum

I am the director of a small museum—a “cabinet of curiosities”—in downtown White River Jct., Vermont. We have exhibited just about everything—even dirt (“silt from the 1927 flood” to be exact.) The collection here includes sea-monsters and Phineas Gage relics, 19th century botanical specimens and Bad Art, Seminole War Diaries and dead cats nestled amid dried flowers, legendary trees that produced lambs and geese, Civil War uniforms and Elvis’s gallstones—even a large number of Victrola records for our “Giant Orthophonic Victrola”. Visitors come to the museum to socialize, read, hear music but above all, to see the objects. Since the categories here include Fauna as well as Flora, I often feel like I’m an object myself and think that visitors to the museum must find me just as odd as some of the artifacts in the collection. It may be a monkey-in-the-zoo scenario, but I wonder if the visitors realize that the objects—and the curator—are looking right back at them with equal curiosity.

White River Junction, A Magnificent Gallery of Debris

White River Junction, Vermont is an abandoned rail center with much of the urban blight one would expect in a much larger town or city. “Rio Blanco” has been host to many things over the years, many of them none-too-savory. A railroad town will always attract a wide spectrum of humanity. The town’s Urban Renewal plans in the 1960s were opposed by enough of the town’s people that they never materialized. However, the construction of two federal interstate highways through town forever transformed the towns economy and left a great many underused or abandoned structures in the wake of Progress. In short, White River Junction was, and is, a modern ruin. It’s the perfect site for an alternative museum.

The museum opened on South Main Street in 1992 and immediately attracted a broad cross-section of citizenry: academics, art professionals, musicians, politicians, journalists, the under-employed, habitual evil-livers, and also quite ordinary people (it might as well be admitted, that many in all of these categories were my own blood relatives). Here then was the first site for the museum. The building was owned at the time by a notorious local slum-lord, but it had been the former home of a renown local restaurant, “Lena’s Lunch”. It was a narrow storefront space which had been a public space for over 100 years—a silent picture theater, indoor miniature golf, and a bowling alley, also a restaurant with transvestite waitresses—yes, submarine sandwiches by day and “Judy” and “Barbara” by night. There ought to be a plaque. Here Elvis impersonators and High-Art all enjoyed equal admiration. (or, High-Art claimed as much admiration as it can, when competing with Elvis impersonators.) Our home was directly across the street from an American Legion Hall; and there are no better critics. They would be completely and utterly potted every night. They withheld nothing.

I decided that a museum of oddities was a good fit with the downtown’s quirky character. I started displaying objects. Simply putting objects on display changed their meaning—it gave them respect even if they had never been respected before. The museum became a kind of self-esteem workshop for unloved objects. People started giving me things. Art. Old cars. Their kids baby-teeth. The hair that they couldn't bear to throw out after haircuts. That's right—hair. Hair in ziplock bags. At first I found it an odd gift. Then I talked to another visitor to the Museum. She grew up in Lebanon, in the Middle-East. And she told me that traditional belief in that part of the world holds hair in utmost importance. After all, if someone should steal your hair, particularly the hair of an infant or young person, they could "put the evil-eye" on the donor of the hair. Then I remembered a Peruvian friend of mine, years ago, who told me that hair-clippings should be safeguarded. His warning was quite specific. It was an admonition against the "evil-eye." Same story, different continents. It got me thinking about stories and how universal they are. The old adage about plots came to mind. Perhaps there are only two plots in the whole world. Either someone comes to town; or someone goes on a trip. Out of this, come all of our stories.

And then of course, the dead cats—they are featured on the museum web-site. They are not true mummies. The are simply dehydrated. Two different people gave me them over two different occasions. I wanted to exhibit them in a way that wouldn't make children cry. I’m not sure if I succeeded. You’ll have to come down and see for yourselves. Like me, you may find that what we save is far less interesting than why we save the things we do. What we do with objects after we have saved them grounds us to the emotional meanings of our world.

If curator and artifacts are sometimes confused within Main Street Museum confines, it is also unclear where the artifacts end and museum display cases, even museum walls and ceilings, begin. And White River Junction itself may be an artifact—a very large, very complex, unaccessioned one,—a kind of giant, hollow, sugar Easter egg,—old and shabby, but with remarkable, if dusty, scenery glued to its insides. This town and this museum have both taught me to love where you are—you may not like where you live, but you ought, at the very least, to love it. And you love a place by knowing it very well. Its history, its things, its people. I hope the Main Street Museum is educational and fun. In our culture, these two concepts are very often mutually exclusive.

“What’s truly saddening is the separation—the Calvinist guilt over fun and where it leads, guilt of our primal, bald-faced, simian desire to stare and marvel and perhaps thereby, oops, learn a thing or two. People do after all, remember the fun they have and it sure beats hell out of the alternative.” —James Taylor, Shocked and Amazed.

We can make our own culture, we can actively participate both in our democracy and in our history. (We’re making history right now, we just don’t realize it.) We can decide the value of things ourselves. We can evaluate the meaning of objects—ourselves. And never, ever let some corporation, or some academic, some magazine article, or some curator—especially some alternative curator—decide what objects are valuable and which objects are not. Don’t assign dollar values to everything. After all—its up to us. What we do with things is much much more interesting than things.

“The love for relics is one which will never be eradicated as long as felling and affection are denizens of the heart. It is a love which is most easily excited in the best and kindliest natures. Who would scoff at this love? Not one!” — Charles Mackay, Memoirs Of Extraordinary Popular Delusions & The Madness of Crowds, London, 1841.

—David Fairbanks Ford, Curator, Main Street Museum

Mr. Ford has been the director of the Main Street Museum since 1992. A member of several old Vermont families, one branch of which are the “poor cousins” of the Fairbanks family of St. Johnsbury who founded the Fairbanks Museum. He has lectured and curated at the Dartmouth College, Norwich University, St. Michaels College and The University of Vermont. However, taking the Sea-Monster to the historic Tunbridge fairgrounds, as well as having his art-car entered in the (now quite historic as well) Tunbridge Demolition Derby must be considered career highlights.